Early Detection/Screening

Why find Breast Cancer early?

Finding breast cancer early means that you have more treatment options and your chances of survival are better. Survival is lower if the cancer has already spread outside the breast when it is diagnosed. As an example, about 9 out of 10 women whose cancer is diagnosed before it has spread outside the breast will be alive 5 years later. However, if the cancer has spread to other parts of the body at diagnosis, only about 2 out of 10 women will be alive 5 years later.

Finding breast cancer early means that you have more treatment options and your chances of survival are better. Survival is lower if the cancer has already spread outside the breast when it is diagnosed. As an example, about 9 out of 10 women whose cancer is diagnosed before it has spread outside the breast will be alive 5 years later. However, if the cancer has spread to other parts of the body at diagnosis, only about 2 out of 10 women will be alive 5 years later.

Detection of breast cancer while it is still small and confined to the breast provides the best chance of effective treatment for women with the disease. Benefits of early detection include increased survival, increased treatment options and improved quality of life. For women, age remains the biggest risk factor in the development of breast cancer with over 70% of cases found in women aged 50 years and older. However, in younger women, tumours are likely to be larger and more aggressive and overall survival is lower than for older women with the disease. It is therefore important that women of all ages understand the importance of finding and treating breast cancer early.

Detection of breast cancer while it is still small and confined to the breast provides the best chance of effective treatment for women with the disease. Benefits of early detection include increased survival, increased treatment options and improved quality of life. For women, age remains the biggest risk factor in the development of breast cancer with over 70% of cases found in women aged 50 years and older. However, in younger women, tumours are likely to be larger and more aggressive and overall survival is lower than for older women with the disease. It is therefore important that women of all ages understand the importance of finding and treating breast cancer early.

Early Detection Methods are

- Breast awareness – awareness by a woman of the normal look and feel of her breasts

- Clinical breast examination – physical examination of an asymptomatic woman’s breasts by a medical or allied health professional

- Screening mammography – use of mammography in asymptomatic women to detect breast cancer at an early stage (BreastScreen Australia is the national mammographic screening program)

- Screening MRI – Since 1 February 2009, a Medicare Benefit is payable for the use of MRI in the surveillance of women under 50 years who have no signs or symptoms of breast cancer but are at high risk of developing the disease. A second Benefit is available if an additional MRI scan is required for the follow-up of any abnormalities detected in the previous 12 months. The Benefits are available to women deemed at ‘high risk’ of breast cancer because of a strong family history of breast or ovarian cancer, or the presence of a high risk gene mutation, as specified in the item descriptor. Women are considered to be at high risk of breast cancer, and therefore eligible for the Medicare rebate, if they meet one of the following criteria for strong family history

- 3 or more first or second degree relatives on the same side of the family diagnosed with breast or ovarian cancer

- 2 or more first or second degree relatives on the same side of the family

diagnosed with breast or ovarian cancer, including any of the following features

- Bilateral breast cancer

- Onset of breast cancer before the age of 40 years

- Onset of ovarian cancer before the age of 50 years

- Breast and ovarian cancer in one relative

- Ashkenazi Jewish ancestry

– Breast cancer in a male relative - 1 first or second degree relative diagnosed with breast cancer at age 45

years or younger, plus another first or second degree relative on the same side of the family with bone or soft tissue sarcoma at age 45 years or younger.

years or younger, plus another first or second degree relative on the same side of the family with bone or soft tissue sarcoma at age 45 years or younger.

Women for whom genetic testing has identified the presence of a high risk breast cancer genetic mutation are also eligible for the rebate due to their high risk of breast cancer.

The criterion for strong family history that has been used by the federal government is based on the definition developed by the National Breast and Ovarian Cancer Centre. The Department of Health and Ageing has developed a series of Questions and Answers on the MRI rebate, available on the Department’s website: www.health.gov.au.

![]() Breast Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI)

Breast Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI)

![]() Consensus Guideline on Diagnostic and Screening Magnetic Resonance Imaging of the Breast

Consensus Guideline on Diagnostic and Screening Magnetic Resonance Imaging of the Breast

![]() The role of breast MRI in clinical practice

The role of breast MRI in clinical practice

Evidence

Breast Awareness

In Australia, even with a fully implemented mammographic screening program, more than half of breast cancers are diagnosed after investigation of a breast change found by the woman or by her doctor. This emphasises the importance of women being aware of the normal look and feel of their breasts and reporting unusual breast changes. Historically, public health campaigns have promoted specific techniques that women should use to examine their breasts (‘breast self-examination’). However, meta-analyses and randomised controlled trials have shown no difference in the size or stage of breast cancers at diagnosis or in the number of deaths from breast cancer for women taught to use a systematic approach for breast self-examination compared with those who did not receive instruction. These trials were conducted in Russia and China and involved large numbers of women. While the applicability of these trials for Australia has been questioned it is unlikely that trials of a similar size will be repeated in the future. It is also unlikely that a suitable control group would be found within the Australian population who have not already been exposed to messages about breast awareness and breast self-examination. A UK study of over 63,000 women aged 45–64 has shown no difference in the number of deaths from breast cancer after 16 years of follow-up between women taught to use a systematic approach to breast self-examination compared with those who did not receive instruction. Thus, while there is evidence that women can find breast changes due to early breast cancer, there is no evidence to promote the use of any one self-examination technique over another.

In Australia, even with a fully implemented mammographic screening program, more than half of breast cancers are diagnosed after investigation of a breast change found by the woman or by her doctor. This emphasises the importance of women being aware of the normal look and feel of their breasts and reporting unusual breast changes. Historically, public health campaigns have promoted specific techniques that women should use to examine their breasts (‘breast self-examination’). However, meta-analyses and randomised controlled trials have shown no difference in the size or stage of breast cancers at diagnosis or in the number of deaths from breast cancer for women taught to use a systematic approach for breast self-examination compared with those who did not receive instruction. These trials were conducted in Russia and China and involved large numbers of women. While the applicability of these trials for Australia has been questioned it is unlikely that trials of a similar size will be repeated in the future. It is also unlikely that a suitable control group would be found within the Australian population who have not already been exposed to messages about breast awareness and breast self-examination. A UK study of over 63,000 women aged 45–64 has shown no difference in the number of deaths from breast cancer after 16 years of follow-up between women taught to use a systematic approach to breast self-examination compared with those who did not receive instruction. Thus, while there is evidence that women can find breast changes due to early breast cancer, there is no evidence to promote the use of any one self-examination technique over another.

Clinical Breast Examination

There is no direct high-quality evidence from clinical trials that population-based screening using clinical breast examination is effective in reducing the number of deaths from breast cancer. No randomised controlled trials have compared screening at a population level using clinical breast examination with no screening, although one is currently underway in India. 15 Studies comparing the combined effects of mammography and clinical breast examination with the effects of mammography alone as a population-based screening tool have shown no difference in the number of deaths from breast cancer in the two groups after more than 15 years of follow-up. Thus, there is no evidence of any additional benefit of clinical breast examination for women who are already attending for regular screening mammography. For women who are not participating in regular mammographic screening, regular clinical breast examination may offer some benefit.

There is no direct high-quality evidence from clinical trials that population-based screening using clinical breast examination is effective in reducing the number of deaths from breast cancer. No randomised controlled trials have compared screening at a population level using clinical breast examination with no screening, although one is currently underway in India. 15 Studies comparing the combined effects of mammography and clinical breast examination with the effects of mammography alone as a population-based screening tool have shown no difference in the number of deaths from breast cancer in the two groups after more than 15 years of follow-up. Thus, there is no evidence of any additional benefit of clinical breast examination for women who are already attending for regular screening mammography. For women who are not participating in regular mammographic screening, regular clinical breast examination may offer some benefit.

Mammography

Population-based screening using mammography is the best early detection method available for reducing deaths from breast cancer. Evidence of the benefit is strongest for women aged 50–69 years. For all women, there is a chance that mammography will either miss a change due to breast cancer (false negative) or that further tests will be performed to examine a change that is not due to breast cancer (false positive). The chance of false negative or false positive results is higher in younger women because their breast tissue is denser, making it more difficult to detect changes. Generally, breasts become less dense as women get older, particularly after the menopause, which is why mammograms become more effective as women get closer to 50 years of age.

Population-based screening using mammography is the best early detection method available for reducing deaths from breast cancer. Evidence of the benefit is strongest for women aged 50–69 years. For all women, there is a chance that mammography will either miss a change due to breast cancer (false negative) or that further tests will be performed to examine a change that is not due to breast cancer (false positive). The chance of false negative or false positive results is higher in younger women because their breast tissue is denser, making it more difficult to detect changes. Generally, breasts become less dense as women get older, particularly after the menopause, which is why mammograms become more effective as women get closer to 50 years of age.

It is estimated that

- Screening 10,000 women aged 50-69 years will prevent about 10-20 deaths from breast cancer over 10 years

- The benefit is similar for women aged 65-74 years where these women do not have other diseases or conditions affecting their survival

- Screening 10,000 women aged 40-49 years will prevent about 5-7 deaths from breast cancer over 10 years

- Screening becomes more effective as women move through the 40-49 year decade.

There is no evidence that population-based screening mammography is beneficial for women younger than 40 years. In these women, the reduced accuracy of mammography produces a high risk of false positive and false negative results

Balancing the benefit

None of the methods described is one hundred percent accurate for the detection of breast cancer – changes due to breast cancer may be missed, or women may undergo a number of investigations to examine a change that is not due to breast cancer. In addition there are individual patient factors that will influence a woman’s decision when weighing up the potential benefits and downsides of any particular screening method. Women may face issues such as the anxiety of waiting for test results, discomfort and inconvenience. In making recommendations to individual women, these issues should be balanced with the potential benefits of each method, taking account of the woman’s age, family history and any personal preference.

Recommendations

Women at population risk*

*Population risk describes the level of risk of developing breast cancer for women in the general population

Breast Awareness

It is recommended that women of all ages, and regardless of whether they attend for mammographic screening, are aware of how their breasts normally look and feel and report any new or unusual changes promptly to their general practitioner. No one method for women to use when checking their breasts is recommended over another.

Changes to look for include

- A new lump or lumpiness especially if it is in one breast

- A nipple discharge

- A change in the size or shape of the breast or nipple

- A change in the skin over the breast such as redness or dimpling

- An unusual persistent pain, especially if it is one breast

Clinical Breast Examination

A firm recommendation regarding clinical breast examination is not possible as there is no evidence to either encourage or discourage the use of clinical breast examination as a screening method for women of any age. Women who are eligible and are attending for regular mammographic screening should be aware that there is no evidence that clinical breast examination will provide additional benefit. Women who are not attending regular mammographic screening may gain some benefit from regular clinical breast examination. Women should discuss their individual needs and preferences with their doctor. Women who are unsure about what is ‘normal’ for them should consult their general practitioner for advice.

A firm recommendation regarding clinical breast examination is not possible as there is no evidence to either encourage or discourage the use of clinical breast examination as a screening method for women of any age. Women who are eligible and are attending for regular mammographic screening should be aware that there is no evidence that clinical breast examination will provide additional benefit. Women who are not attending regular mammographic screening may gain some benefit from regular clinical breast examination. Women should discuss their individual needs and preferences with their doctor. Women who are unsure about what is ‘normal’ for them should consult their general practitioner for advice.

Mammographic Screening

- Women younger than 40 years

Mammographic screening is not recommended for women younger than 40 years of age - Women aged 40–49 years

Women aged 40–49 years are eligible for free two-yearly screening mammograms through the BreastScreen Australia Program (although they are not targeted by the Program). In deciding whether to attend for screening mammography, women in this age group should balance the potential benefits and downsides for them, considering the evidence that screening mammography is less effective for women in this age group than for older women - Women aged 50–69 years

It is recommended that women aged 50–69 years attend the BreastScreen Australia Program for free two-yearly screening mammograms - Women aged 70 years and older

Women aged 70 years and older are eligible for free two-yearly screening mammograms through the BreastScreen Australia Program (although they are not targeted by the Program). In deciding whether to attend for mammographic screening, women in this age group should balance the potential benefits and downsides of attending for them, considering their general health and whether they have other diseases or conditions that may impact on their decision. General practitioners should discuss with all eligible women the possible outcomes of mammographic screening (both positive and negative) for them

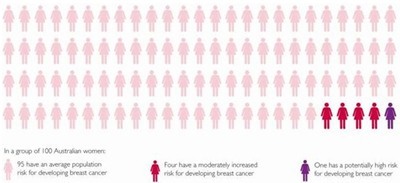

Women at Increased Risk of Developing Breast Cancer

Women are at increased risk of developing breast cancer if they have a strong family history of breast or ovarian cancer (two or more family members have had breast or ovarian cancer, especially if they are close relatives – mother, sister or daughter – and/or if they were younger than 50 when their cancer was diagnosed), are a carrier of a gene mutation known to predispose to breast cancer or have previously been diagnosed with invasive breast cancer, ductal carcinoma in situ or other high-risk pre-invasive breast disease. The risk of developing breast cancer for an individual woman can change as different life events unfold.

For women of all ages who are at increased risk of developing breast cancer it is recommended that an individualised surveillance program be developed in consultation with the woman’s general practitioner and/or specialist. This might include regular clinical breast examination and breast imaging with mammography, ultrasound and /or MRI. Women should also be aware of the normal look and feel of their breasts and report any changes promptly to their general practitioner or specialist irrespective of whether they are having regular follow-up tests/examinations.

For women of all ages who are at increased risk of developing breast cancer it is recommended that an individualised surveillance program be developed in consultation with the woman’s general practitioner and/or specialist. This might include regular clinical breast examination and breast imaging with mammography, ultrasound and /or MRI. Women should also be aware of the normal look and feel of their breasts and report any changes promptly to their general practitioner or specialist irrespective of whether they are having regular follow-up tests/examinations.

Genetic Clinics

Family cancer clinics provide a service for people with a family history of cancer and their health professionals. After collecting and thoroughly assessing detailed information about a woman’s family history of cancer these clinics provide:

Family cancer clinics provide a service for people with a family history of cancer and their health professionals. After collecting and thoroughly assessing detailed information about a woman’s family history of cancer these clinics provide:

- Information about a person’s risk of developing cancer

- An estimate of the likelihood of carrying an inherited mutation in a cancer predisposing gene

- Counselling and support

- Advice about possible strategies that might help reduce the risk of cancer

- Information about early detection of cancer

- If appropriate, the offer of genetic testing

You will need the Adobe Reader to view and print these documents.

![]()