Risk

What is risk?

Risk measures the chance of something happening. There are a number of ways in which risk is represented. Risk is commonly communicated, by healthcare professionals and the mass media, in two ways – relative risk and absolute risk.

- Relative risk: the likelihood of something happening to people exposed to a particular risk, compared to those not exposed to that risk

- Absolute risk: the chances of something happening to a person over a period of time

- Assuming you live to age 90, your risk of getting breast cancer over your lifetime is about 12%. That might sound scary, because it means that an average of about 1 out of every 7 women will get breast cancer over a 90-year life span

- You can also look at it another way: A 12% risk means there’s an 88% chance that you WON’T get breast cancer

- Knowing what factors can increase or decrease your risk for breast cancer is important. But you probably want to know just HOW MUCH those factors change your risk

- If you hear that a certain treatment can reduce your risk by 40%, what does that mean?

- To understand what the numbers mean about YOUR risk for breast cancer, the key terms to know are relative risk and absolute risk

- Relative risk is the number that tells you how much something you do, such as taking a pill, can change your risk compared to your risk without taking that pill. Relative risk can be expressed in percentages and in “hazard ratios.” If you do nothing new, your hazard ratio is 1.0 – this means that your risk doesn’t change. If you do something and your risk decreases by half, or goes down to 0.5, then you are half as likely to have the risk. But if your risk goes up, from 1.0 to 1.88, then you are 88% more likely to encounter the risk. If your risk goes up to 3.0, then you have a threefold (300%) increased risk of having the problem

- Absolute risk is the size of your own risk. Absolute risk reduction is the number of percentage points by which your own risk changes if you do something, like taking a pill. The size of your absolute risk reduction depends on what your risk is to begin with

Example of risk going down for a woman with breast cancer history

Suppose you have had breast cancer and had lumpectomy with clear margins (meaning no cancer was found between the tumor and the edge of the surrounding tissue that was removed along with it).

After lumpectomy with clear margins, your risk of the breast cancer coming back in the same breast is about 30%. But if you choose to have radiation therapy after your lumpectomy, you can reduce your risk of the cancer coming back by two-thirds, or 66%. This is the relative risk decrease.

But how much of a difference does radiation’s 66% drop really make? To figure out the change to your absolute risk , take two-thirds off your risk of 30%

- Multiply your risk of the cancer coming back (30%) by the relative risk decrease from radiation therapy (66%), and you get a decrease of 20% (30% x 66% = 19.80% or 20%)

- To figure out your remaining risk of recurrence after radiation, subtract the 20% from the 30% risk of recurrence that you started out with (30% – 20% = 10%). So your absolute risk of the cancer coming back falls to 10% if you have radiation therapy

Now, after lumpectomy and radiation, is there something else you can do to knock down the 10% risk further? You may also choose to take hormonal therapy (for example, tamoxifen or an aromatase inhibitor) for 5 years. If you do that, you can reduce your risk by another 50%. By taking hormonal therapy for 5 years, you lower your relative risk of the cancer coming back in the same breast by half, or 50%. To see how big a difference hormonal therapy makes in your absolute risk , take half off your risk:

- Multiply your risk by the relative risk decrease from tamoxifen (10% x 50% = 5%)

- Then subtract that 5% from your risk (10% – 5% = 5%)

Now your absolute risk of the cancer coming back is 5%. So by having radiation therapy and taking hormonal therapy for 5 years, you have reduced your risk of the breast cancer recurring from 30% to 5%.

As another example of risk, women in their 50s taking hormone replacement therapy (HRT) for five or more years for the management of menopause symptoms could be said to be at 35% increased risk of breast cancer over women who do not use HRT. In other words, the risk has increased from 11 in 1000 women to 15 in 1000 women. This is an increase of 35%, but in real terms it is only 4 extra women in 1000 – or 0.4% absolute risk.

| Over five years, of 1000 women in their 50s who DO NOT take HRT, 11 women may get breast cancer . |

Over five years, of 1000 women in their 50s who DO take HRT, 15 women may get breast cancer . In other words, there will be 4 extra cases of breast cancer in HRT users compared to non-HRT users. |

|

|

|

Knowing how much your breast cancer risk changes with lifestyle changes and treatment options can help you and your doctor make the best decisions for You.

Risk Factors

One in nine women in Australia will develop breast cancer in their lifetime.

Generally it is not possible to determine what causes breast cancer in any individual woman. However, studies looking at very large numbers of women have shown there are some characteristics that are more common among groups of women who have developed breast cancer compared to groups of women who have not. These are called risk factors .

- Personal characteristics

- Family history

- Factors relating to the breast

- Hormones and menstrual history

- Lifestyle & health

Having certain risk factors increases a woman’s chance of developing breast cancer.

Some of the risk factors for breast cancer include growing older, having a strong family history of the disease, being overweight, drinking alcohol and other lifestyle and environmental factors. Some of these factors are beyond your control but there are some things you can change.

However, having one or more risk factors for breast cancer does not mean you will get breast cancer. And many women who develop breast cancer have no obvious risk factors.

On the other hand there have been some factors that are thought to have a protective effect against breast cancer, like having children at a younger age and breastfeeding. However, women with protective factors may still develop breast cancer.

Gender

Being a woman is the main risk factor for breast cancer. Women are 100 times more likely to develop breast cancer than men.

Age

Increasing age is one of the strongest risk factors for developing breast cancer.

Breast cancer can occur in younger women, but about three out of four breast cancer cases occur in women aged 50 years and older.

About one in 250 women in their 30s will develop breast cancer in the next ten years. This compares to about one in 30 for women in their 70s.

Height

Being 175cm or taller is associated with a slightly increased risk for breast cancer.

Weight

The relationship between weight and breast cancer risk depends on whether you are pre or post-menopausal.

Before menopause, women who are overweight are less likely to develop breast cancer than lean women. After menopause, breast cancer risk increases with increasing weight or body mass index (BMI).

Your BMI is calculated using your weight and height measurements. It can be used to determine if you are at a healthy weight, overweight, or obese. A BMI from 18.5 to 24.9 is considered a healthy weight range. A BMI between 25 and 29.9 is considered overweight, and a BMI of 30 or more is considered obese.

Affluence

Breast cancer occurs more frequently in women who live in more affluent areas. This probably relates to lifestyle factors.

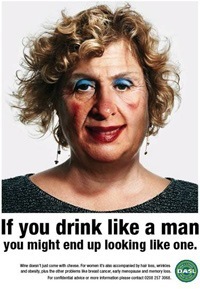

Alcohol Consumption

Alcohol Consumption

Drinking more than two glasses of alcohol each day is associated with an increased risk of breast cancer. This includes beer, wine and spirits. Your risk increases with each additional 10g of alcohol intake per day.

Hodgkin’s Disease

Breast cancer occurs more frequently in women who have had Hodgkin’s disease as a consequence of treatment with radiation and/or chemotherapy.

Exposure to high levels of ionising radiation

High dose ionising radiation, as is experienced with some cancer treatments and in certain environments, is associated with increased breast cancer risk. The highest risks are associated with an earlier age of exposure.

Regular Physical Activity

Active women of all ages are at reduced risk of breast cancer compared to women who do not exercise.

The exact amount of physical activity needed to reduce your risk is not yet clear. However, studies have shown that one and a half to four hours per week of brisk walking (or equivalent) reduces the risk of breast cancer in post-menopausal women. And the more exercise you do, the bigger the benefits in lowering your risk.

Child-Bearing

Having children is associated with a decreased risk of breast cancer. The more children women have, the more their risk of breast cancer appears to be reduced.

Among women who have had children, having them at a younger age (less than 30 years) is associated with lower breast cancer risk.

Breast Feeding

Breastfeeding for a total of 12 months or longer can slightly reduce your breast cancer risk.

Strong Family History

The significance of a family history of breast cancer increases with

- The number of family members affected

- The younger their ages at diagnosis

- The closer the affected relatives are related to you

The increase in risk is fairly small unless there are three or more first or second-degree relatives on the same side of the family with breast or ovarian cancer. It is important to note that a family history on your father’s side is just as important as it is on your mother’s side of the family.

The risk is stronger if two or more relatives have other characteristics associated with increased risk, such as being diagnosed before age 50 or being of Ashkenazi Jewish descent.

Although women who have one or more first-degree relatives with a history of breast cancer are at increased risk, most will never develop breast cancer. Of those women with a family history who do develop breast cancer, most will be older than 50 years when their cancer is diagnosed.

Despite the importance of family history as a risk factor, eight out of nine women who develop breast cancer do not have an affected mother, sister, or daughter.

Inherited Genetic Factors

Breast or ovarian cancer caused by inheriting a faulty gene is called hereditary cancer. We all inherit a set of genes from each of our parents. Sometimes there is a fault in one copy of a gene which stops that gene working properly. This fault is called a mutation.

There are several gene mutations that may be involved in the development of breast or ovarian cancer. The most common mutations are in the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes. These are genes that normally prevent a woman developing breast or ovarian cancer. However, mutations in these genes increase a woman’s risk of developing breast cancer.

Ashkenazi is the term used to refer to Jews who have ancestors from Eastern or Central Europe, such as Germany, Poland, Hungary, Lithuania, Ukraine or Russia. As Ashkenazi Jews descend from a small population group, they have more genes in common than the general population.

While people of Ashkenazi Jewish descent don’t have any more faulty genes than anyone else, they do have a high prevalence of some gene faults and very low levels of others. Three gene faults associated with increased risk of breast and ovarian cancer have been found to be one of the genetic traits which are more common amongst Ashkenazi Jews than the general population. These gene faults occur in two per cent of Ashkenazi Jews compared to 0.2 per cent of the general population.

While people of Ashkenazi Jewish descent don’t have any more faulty genes than anyone else, they do have a high prevalence of some gene faults and very low levels of others. Three gene faults associated with increased risk of breast and ovarian cancer have been found to be one of the genetic traits which are more common amongst Ashkenazi Jews than the general population. These gene faults occur in two per cent of Ashkenazi Jews compared to 0.2 per cent of the general population.

Factors relating to the breast itself

A previous breast condition Being previously diagnosed with a non-invasive breast condition such as ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) or lobular carcinoma in situ (LCIS), is associated with an increased risk of developing invasive breast cancer.

Breast Density

Women with ‘dense’ breasts are more likely to be diagnosed with breast cancer than women with less ‘dense’ breasts.

Your breast density is something that can be measured on a mammogram. A mammogram of a woman with dense breasts will appear much like white cotton wool. A mammogram of a woman with less dense breasts will appear more grey and transparent. Breast density cannot be measured by physical breast examination.

Although breast density decreases with age and after menopause, there is a large difference in breast density across women of the same age.

Common Misconceptions

There are a number of “myths” about the risk factors and causes of breast cancer that sound plausible but have little or no scientific theory or data to support them.

There is no body of evidence that an increased risk for breast cancer can be attributed to

- The use of antiperspirants

- Wearing a bra

- A blow or injury to the breast

- Drinking milk

- Having silicone breast implants

- Having a mammogram

Breast Cancer Myths – how are they generated?

The origin of most myths is not known, but the Internet and email has helped spread many of them. It is natural for people to look for an explanation that is easily understood about why they or a loved one has breast cancer. Many myths are attractive because they seem to offer a course of action that could help reduce the risk of breast cancer.

How to Distinguish Fact from Fiction

It is not always easy to distinguish fact from fiction and myth from reality, especially if you are not an expert in science and medicine. It is important that people are not unduly worried or misled by information about breast cancer.

The use of Antiperspirants

Is wearing deodorant linked to breast cancer?

There have been claims that using antiperspirant deodorant can cause breast cancer. This is based around a theory that antiperspirants cause toxins to build up in the lymph glands of the armpit, which then cause cancer in the breast tissue. Other people worry about chemicals contained in deodorants getting into the body through the skin and travelling to the breasts.

There is no quality evidence which shows the use of antiperspirant deodorants is associated with or causes breast cancer.

Wearing a Bra

This explanation for the higher rates of breast cancer in developed countries was generated by Sydney Ross Singer and Soma Grismaijer, a husband and wife anthropology team, in their book “Dressed to Kill”, published in 1995. They claim that tight-fitting bras constrict the lymph system, causing toxins to accumulate in the breasts and cause cancer.

This is not based on a credible hypothesis, for many of the reasons outlined in The use of antiperspirants and because lack of blood supply or increased pressure is not what causes normal cells to become cancerous. Although these researchers included some data from studies in their book to link bra wearing with breast cancer, these data have not been subject to peer review and have been criticised for lack of appropriate scientific controls.

There is a possible link between large breast size and an increased risk for breast cancer in post-menopausal women, but this is accounted for in part by the fact that obesity is a risk factor for breast cancer.

A Blow or Injury to the Breast

A blow or injury to the breast does not cause breast cancer, but it can draw attention to a pre-existing lump. An injury can damage tissue and blood supplies, but does not damage the genetic material in the cells. It is errors in the replication of this genetic material that is the basis for the development of a cancer cell from a normal cell.

Drinking Milk

There have been a number of claims that the consumption of cows’ milk can increase the risk for breast cancer. There are several issues to consider.

- There is some evidence that drinking milk with a high fat content may increase the risk of breast cancer, but this is thought to be due to the link between obesity and breast cancer as drinking skim milk seems to protect against cancer

- Certain chemicals and pesticides, some of which have been shown to cause cancer, do show up as contaminants in both cows’ milk and human milk. At this time there is no strong evidence to link these chemicals with increased risk for breast cancer, although this cannot be excluded. In Australia the levels of these contaminants in milk products is subject to testing and regulation

- An argument is made that cows treated with bovine growth hormone (BST) have increased levels of a chemical called insulin-like growth factor (IGF-1) in their milk, and high blood levels of IGF-1 in humans have been linked with breast and prostate cancers. However it is not known if IGF-1 found in cows’ milk can affect humans. More importantly, the use of BST is currently banned in Australia

- Additional claims that oestrogen in cows’ milk can affect women’s breast tissue and cause cancer or that other, unspecified, milk compounds can cause oestrogen release in women have not been substantiated

Silicone Breast Implants

Silicone breast implants are not linked to breast cancer risk. A large study on the long-term effects followed women with silicone breast implants for more than 10 years and showed no increased risk.

Some earlier studies of shorter duration actually showed exposure to implants reduced a woman’s risk for breast cancer.

The guidelines for breast health and screening are also applicable to women with breast implants.

Mammograms

The known benefits of mammograms in the early detection of cancer far outweigh the very small potential risks of them causing cancer. The potential risk exists because exposure to ionising radiation can cause cancer. However given the limited number of mammograms a woman has in her lifetime, and the standards of the mammographic equipment in use today, the increased radiation exposure from a mammogram is no more than that from taking a plane flight across Australia.

Substantial exposure to X-rays, especially in childhood, is associated with an increased risk of cancer in later life. In the past, women who received treatment for scoliosis (curvature of the spine) in childhood and adolescence, have been shown to have an increased risk of dying of breast cancer. Today, more care is taken with these treatments and this is less likely to be the case.

Risk factors for breast – cancer a review of the evidence 2018

Breast Cancer Risk and Prevention